Integrating environmental and ecosystem health into One Health – choices, contexts and communities matter

Our societies are facing major challenges, many caused by the ever-expanding human footprint on the planet. These challenges, such as ecosystem degradation, food system failures, biodiversity loss, infectious disease emergence, extreme climatic events and antimicrobial resistance, collectively impact on the health of ecosystems, people, animals and plants across the world, with a disproportionate impact in the least-developed countries.

The One Health approach is seen to deliver collaborative and systemic responses to some of these complex societal threats by promoting more inter-sectoral and inter-disciplinary collaboration across the environment, human, plant and animal health sectors. This is expected to improve the health of humans, animals, plants, and the environment, while contributing to sustainable development.

Most discussions around One Health tend to centre around human and animal health with environmental dimensions rarely unpacked and discussed in detail. In East and Southern Africa, as elsewhere, this is a serious issue as it risks leaving out key actors and agendas, leading to unintended negative outcomes and missed opportunities.

The members of the One Health ‘Quadripartite’ – the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) – that guide the transformations required to mitigate the impact of current and future health challenges at human–animal– plant–environment interfaces, recognize this challenge and have called for the environment to be fully integrated into the One Health approach. While they suggest several ways to do this – such as integrating environmental experts in One Health fora and platforms, incorporating environmental data into One Health decision-making, fostering a better understanding of environmental issues and ecosystem health in the One Health community, and boosting the capacity of the environmental sector and its institutions to have an equal voice at the One Health table and in decision-making – most countries are yet to make strong progress in this area.

To advance this agenda, the Capacitating One Health in Eastern and Southern Africa (COHESA) project recently brought together representatives of ministries of health, agriculture and the environment, members of country national One Health platforms and academics and international experts in different health components from across the region to brainstorm how best to integrate environment and ecosystem health (EEH) within the wider One Health concept in the 12 project target countries in Eastern and Southern Africa. This effort aligns with the quadripartite Action track 6 of the Joint Plan of Action which identified the need to better ‘integrate the environment into One Health.’

Convened in Hwange, Zimbabwe, by the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD), one of the consortium members of the COHESA project, the three-day workshop mapped and co-defined core dimensions of environment and ecosystem health, articulating intersections, interdependencies, trade-offs and relations among EEH and other One Health components.

On the third day, at country level, participants started to develop strategies to better identify and engage EEH actors, stakeholders and practitioners as well as understand their interests, needs, roles, opportunities and motivations, in order to fully integrate them in national One Health platforms and initiatives.

Field visits to nearby community projects linked to the Zone Atelier Hwange and the ‘Production and Conservation in Partnership’ research platform as well as observation of interactions between people and the nearby Hwange National Park also stimulated lively discussion and reflection on the different ‘healths’ – of people, ecosystems, livelihoods – observed trade-offs and the implications of community choices on outcomes. Again, the tension was visible between achieving healthier ecosystems, perhaps at the expense of people’s livelihoods, and creating economic opportunities with minimal environmental damage or negative side-effects.

For the COHESA teams developing country-level strategies, these points have several implications:

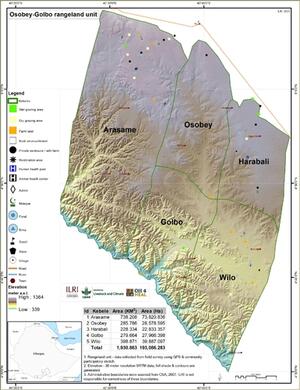

Managing complexity: The presentations, visits and mapping exercises showed how EEH is characterized by the always evolving nature and diversity of disciplines, actors, themes and issues that comprise the environment, making its integration and implementation within the One Health context complex. Inclusion of components such as animal, wildlife, plant, soil, air and water health, forests and rangelands health, and involvement of a wide scope of stakeholders, need to be considered when discussing integration and roles of the environment and ecosystem health into implementation of the One Health approach.

Whose health: Health was seen to be not only ‘about diseases’ but also about well-being and quality of life – applied to people, animals and ecosystems and indeed the many different components such as wildlife, water, plants and soil. Together, these notions of well-being and health, already present in the WHO definition of human health, were felt to provide a useful overarching and holistic framework with deep roots in systems thinking.

Managing trade-offs: As introduced above, the perceived role of the environment and its health in the One Health approach needs to be revisited; from being considered as a source of exposure or risk to animal and human health, to an outcome of interest when managing human and animal health issues. Participants noted that the environment is associated with both negative and positive impacts from human and animal activities such as industrialization and production systems, land use practices resulting in positive outcomes like improved livelihoods, research, tourism, recreation, trade and travel, traditional drug production and spiritual well-being. Unfortunately, there is a high impact from the negative outcomes such as climate change, environmental degradation, biodiversity loss, pollution, disease outbreaks, challenges to animal and plant welfare. Human-wildlife conflicts resulting from habitat fragmentation, and civil unrest among other problems are far reaching.

Contexts are critical: Owing to this complexity, successful implementation of One Health, including the integration of environment and ecosystem health, requires context-specific approaches, and a willingness by all the disciplines and stakeholders to collaborate and make tradeoffs, in order to reach a situation that is most harmonious in terms of balancing the health of humans, animals and environments with a view to maximize the well-being of society and the ecosystems within which society exists.

Communities matter: People and communities living closest to nature and areas rich in biodiversity often suffer the brunt of conservation efforts. This is particularly true in the savannas of eastern and southern Africa hosting large, protected areas with healthy wildlife populations but also small-scale farmers with limited livelihood options in a semi-arid environment. The people-nature interfaces in these savannas need to be managed for the benefit of people and nature, and not one at the expense of the other.

Participants proposed the development of protocols to empower and support the socio-economic development of these communities as a way of promoting effective long-term conservation of biodiversity. Indigenous knowledge, beliefs and practices that have been used for generations and passed on through cultural value systems and practices to promote biodiversity conservation constitute a key component of environment and ecosystem health. Unfortunately, this knowledge is at risk of erosion from factors such as technology and science, globalization, global warming, modernization, religion and forms of communication coming from the developed world, among others.

Ways forward

Following the mapping exercises, the 12 COHESA target countries will further develop their country EEH strategies focusing on their local contexts; ensuring inclusion of previously misunderstood and under-represented issues, themes and actors. These will be incorporated in the existing country OH strategies and platforms or the ones that are being developed, in countries where they do not exist. The biodiversity conservation, environmental, public health and animal health/veterinary sectors will collaborate to deliver on this.

More

Watch video recordings of the plenary presentations

Download event presentations and country posters here

About COHESA

The project ‘Capacitating One Health in Eastern and Southern Africa (COHESA)’ is co-funded by the OACPS Research and Innovation Programme, a program implemented by the Organization of African, Caribbean and Pacific states (OACPS) with the financial support of the European Union.

COHESA is led by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD - Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement) and the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) Africentre.