Promises and pitfalls of making livestock vaccination more accessible

In August and September 2023, about 136,000 cattle, camels, goats and sheep were vaccinated against Rift Valley fever (RVF) in Isiolo County, Kenya.

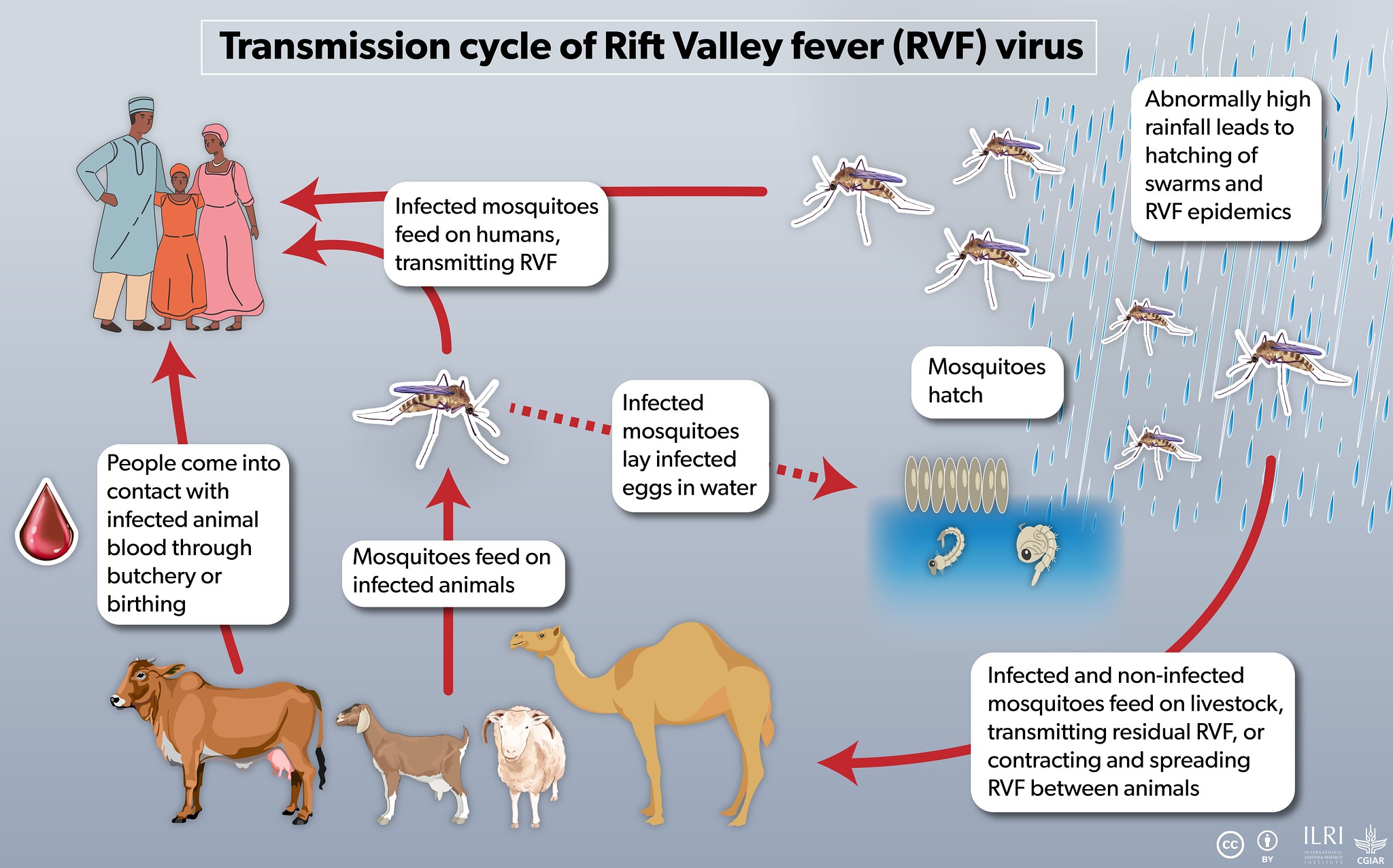

This was good news because RVF is a viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes that can affect livestock and humans, and Isiolo County is prone to outbreaks that have been deadly in the past.

With El Niño forecasted to bring more rain than usual to Kenya (more rain means more mosquitoes), this campaign attempted to address concerns that more RVF outbreaks could follow.

Behind the scenes of the vaccination campaign, researchers at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) were asking additional questions to ensure that both men and women livestock farmers can equally get their livestock vaccinated to decrease exposure to RVF.

How can we modify livestock vaccination campaigns to be more accessible and does running a more accessible campaign increase vaccination coverage?

This article shares the results of a study designed to measure the impact of making RVF vaccination more accessible to women livestock keepers.

Despite facing challenges measuring impact, the team learned how many women are contributing in modest ways to getting their households’ animals vaccinated.

Why is it harder for women to get their livestock vaccinated?

In an earlier phase of the project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), women and men livestock keepers in Kenya and Uganda described the barriers they experienced in accessing vaccines.

In some locations, women described challenges to getting information about the vaccine campaign.

They also had limited decision-making ability due to livestock ownership patterns where men are the primary decision-makers, limiting women’s ability to access vaccines.

Gender norms vary from place to place, so a baseline activity before the vaccination campaigns identified barriers specific to women in Isiolo County.

These included:

- the cost to find or hire help to move animals;

- being bypassed by men in the queue;

- worrying that vaccines may run out after travelling to the vaccination point;

- not receiving information in time;

- balancing vaccination and household responsibilities such as cooking and childcare;

- challenges restraining cattle and camels;

- risk of animal injury at the vaccination point;

- vaccine side effects (especially abortion); and

- vaccination is perceived as a man’s activity, with the exception of female heads of household.

Even when some barriers, such as challenges restraining large animals during vaccination or concerns about vaccine side effects, were shared by men and women, they were experienced more acutely by women.

Women often have less authority to delegate other household members to take animals for vaccination than men.

If a woman cannot ask more people to accompany her to the vaccination drive, it can be even more physically demanding to control the animals while waiting.

Furthermore, because she is viewed as weaker than men, she is exposed to more intimidation once in the vaccine queue.

These challenges, not having sufficient labour and staying longer at the crowded vaccination event, can stress animals and make them increasingly difficult to manage.

How did we prepare for this vaccination event?

In collaboration with the Isiolo County Government, the implementors of the vaccination campaign, ILRI developed a set of modifications to address as many of these barriers as possible in half of the vaccination sites.

To address women not receiving information on time, the team identified three women champions at each intervention location and incentivized them to share information with other women by attending women’s groups one week ahead of the planned vaccination.

In addition to engaging the community disease reporter to identify and inform women-headed households about the vaccination, there were women’s only informational sessions about RVF vaccines led by veterinarians.

To address challenges with bypassing in the queues and restraining animals, makeshift pens and crushes to restrain and guide animals were built ahead of time.

Increased numbers of vaccinators were hired so camels and cattle could be vaccinated separately from small ruminants to prevent animal injury.

Local leaders were asked to share the following messages when communicating about the upcoming campaign: ‘First come, first served’, ‘More vaccinators, enough vaccine, shorter time to vaccinate’ and ‘Women also have a responsibility to ensure animals remain healthy’.

Some modifications proposed by the team organizing vaccination and livestock keepers themselves in the baseline activity were not feasible, such as communicating via radio because it was not possible to exclude the control site.

Furthermore, the short time frame of the project did not allow discussion or challenging of gender norms around livestock decision-making that may limit women from engaging in livestock vaccination.

On the vaccination days, veterinary and public health students interning with Isiolo County administered a short questionnaire to anyone bringing animals, with questions about the gender of the head of household and if a woman in the household where the animals came from had participated in deciding whether the animals should be vaccinated or contributed financially in any way.

What did we learn from the study?

As they say, even the best-laid plans can go awry.

Preliminary data show the control sites performed better or the same as the intervention sites for most of the metrics used to measure the impact of the gender-responsive modifications.

These metrics included proportions of women bringing animals, representation of women-headed households, numbers of small ruminants vaccinated and reports of women in the represented households contributing to vaccination in any way.

This is the opposite of what was expected; the team hoped these metrics would be better in the sites with the gender-responsive modifications.

So, what happened? For logistical reasons, the vaccination teams chose to begin with the intervention sites, where they were met with two challenges.

First, there was a delay in receiving the RVF vaccines.

Distribution of RVF vaccines is strictly regulated in Kenya, with requirements to purchase including a letter from the County Directorate of Veterinary Services documenting that RVF is present in the area where the vaccine will be used.

Second, livestock keepers voiced concerns about side effects, especially abortions at a time of year when many animals are pregnant, and some chose not to vaccinate.

By the time the vaccination team began the control sites, the vaccines were ready by the anticipated start date and the treatment sites had not reported any abortions.

This news spread through social and family networks to the control sites, boosting confidence in the vaccine.

The vaccination team even reported calls from livestock keepers at the intervention sites asking for them to return (which was not possible) and a few cases of livestock keepers with the financial means travelling with their animals to the control site to vaccinate after they had opted not to vaccinate when it was available in their area a few weeks prior.

In short, it was not possible to determine any effects of the modifications beyond knowing they were less impactful than the logistical challenges and widespread fear of side effects.

Do these results mean it is not worth the extra effort to modify vaccination campaigns to increase accessibility? Not necessarily.

The gendered barriers livestock keepers reported still exist even if the research team was unable to measure them.

In future studies, pairing the quantitative indicators, such as those measured at the vaccination event, with qualitative indicators measured later at the individual or household level would assess the impact of the modifications.

In the same way that disease problems in livestock become more visible after the dominant disease is controlled, gendered barriers to vaccination can be masked by other factors, such as late vaccines and worries about side effects.

What else was learned from this activity?

First, the involvement of women in vaccination was very high; about three-quarters of the respondents interviewed at the vaccination campaign reported that a woman in the household where the animals had come from participated in vaccination in some way.

The most common examples included waking up earlier than usual to prepare tea for herders or household members taking the animals to the vaccination point, helping to move animals and contributing money to purchase food or water for those moving animals.

This suggests that women in Isiolo County want to have their animals vaccinated and support vaccination activities in ways that comply with the gender norms in their communities.

Other research projects such as Women Rear have gone a step further to increase vaccination by challenging restrictive gender norms that prevent women from accessing vaccines, which is another strategy to consider in future projects.

Second, the high turnout in the control sites highlighted the power of word of mouth in tight-knit communities to either encourage or dissuade fellow livestock keepers from vaccinating.

Last, the challenges the project experienced in getting RVF vaccines suggest that it may be useful to reassess the regulations governing the distribution of these vaccines in Kenya to ensure they are used properly but without providing unnecessary barriers that limit use.

Next steps

We look forward to future studies that continue to make visible the layered barriers some community members, especially women, face in accessing vaccines and measuring the impact of modifications to vaccination campaigns designed to increase access.

We thank Adan Abdi, Alessandra Galiè and Bernard Bett for their contributions to this blog. The research was funded by USAID, grant number 720BHA22IO00221.

You may also like

Related Publications

Harnessing community conversations for gender-responsive engagement in livestock management in Ethiopia: a methodological reflection

- Lemma, Mamusha

- Alemu, Biruk

- Knight-Jones, Theodore J.D.

CGIAR Science Program on Sustainable Animal and Aquatic Foods : Gender, youth and social inclusion area of work

- Achandi, Esther L.

Effects of livestock related gender roles on pastoral children and their implication to RVF risk exposure

- Mutambo, Irene N.

- Bett, Bernard

- Bukachi, S.A.