Working across institutions and disciplines for science-based responses to fight COVID-19 in Ethiopia

Ethiopia recorded its first case of COVID-19 on March 13, 2020 and the disease has been spreading steadily since then, giving rise to concern over grave health consequences and harsh economic impacts. By June 11, 2,670 cases were recorded across different regions of the country, with a majority in Addis Ababa, the capital.

The true number of cases may be much higher and increased testing will be key to tracking and containing the disease’s spread.

But Ethiopia, like many nations in Africa, faces challenges in deploying testing at scale, which global health professionals consider key to managing, tracking and containing the spread of the virus.

Scientists from CGIAR, including the International Livestock Research Institute and Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, have been working with national partners to develop solutions that highlight how agriculture expertise can be adapted to support efforts to mitigate the pandemic in Ethiopia.

They proposed two out-of-the-box ideas and complementary activities that aim to better target and use limited resources. First, the group assessed the feasibility to carry out COVID-19 pooled sample testing. They then proposed a method using geospatial analysis to map and identify hotspot areas where COVID-19 mass testing can be prioritized.

Both were presented to the Ethiopia Ministry of Health for further consideration. Coincidentally, scientists at Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI) were working on optimizing the pooling method for laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19. The technical support from ILRI to help optimize the pooling protocol was embraced by the Armauer scientists immediately. The ministry pledged its commitment for implementing the protocol while scientists from AHRI and ILRI provide technical support and monitoring.

“It’s critical to make science-based informed decisions during this pandemic,” said Abebe Genetu, the director general of AHRI. “The pooled sample testing method complemented with zonation is critical because they allow us to target our efforts in potential hotspot areas, which will save us both resources and time as well as being efficient in our fight against COVID-19.”

Pooled testing to increase efficiency

Given Ethiopia’s relatively low caseload when compared to other countries, a pooled sampling procedure could expedite testing and minimize turn-around times. Pooled testing is a procedure commonly used to increase efficiency and cost-effectiveness by mass testing of people. It has been used extensively with other diseases such as HIV-AIDS and hepatitis.

The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) has experience in using pooled sample testing methods in its research programs. As Tadelle Dessie, a principal scientist at ILRI, said, “We were looking for ways we could use our expertise to support government efforts and after consulting senior experts at ILRI, this looked like a good option.”

Pilot testing was started by a team led by Andargachew Mulu, a virologist at AHRI, using the pooled sample testing method. Initially, they tested the optimization from three samples in one pool and increased to ten samples in one pool. According to Andargachew, “It was found that four samples in one pool is optimal for fast screening that does not lose test sensitivity. It is estimated this can increase testing efficiency by almost 300 percent, with turnaround times reduced to 12 hours from 36 hours.”

This is good for testing in areas within Addis and beyond. A group of samples, for example, could be processed together—saving time and reagents—to determine if an area within the city had cases of the disease. A negative result would essentially ‘clear’ an area (at least temporarily) while a positive result would then lead to individual testing and contact tracing in the affected area. This process would increase efficiencies as long as the overall caseloads remain low.

Mapping priorities

To best identify areas where mass sampling and other priorities could be channeled, another group of scientists used their expertise in geospatial planning and analysis in locating hotspots that would help streamline responses to localized outbreaks.

“With the support of GIZ, the German development agency, we have been working a long time with the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) and the Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture to support Ethiopia’s agricultural transformation agenda through improved data sharing and analytics,” said Lulseged Tamene, a senior scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. “When the COVID-19 pandemic first reached Africa, the team started exploring potential support and the opportunity came with mass testing, which cannot be done everywhere for logistical and financial reasons. We were asked to see if we could help to find ways to prioritize where this would take place.”

The coalition of scientists working on these proposals includes individuals from ILRI, the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, and national institutes including AHRI, EIAR, the Water and Land Resource Center (WLRC) and Addis Ababa University (AAU).

The team is currently working on three methods: 1) mapping hotspots to focus mass testing, 2) spatial and temporal prediction of COVID-19 to model its outbreak and spread and 3) contact tracing through mobile phones.

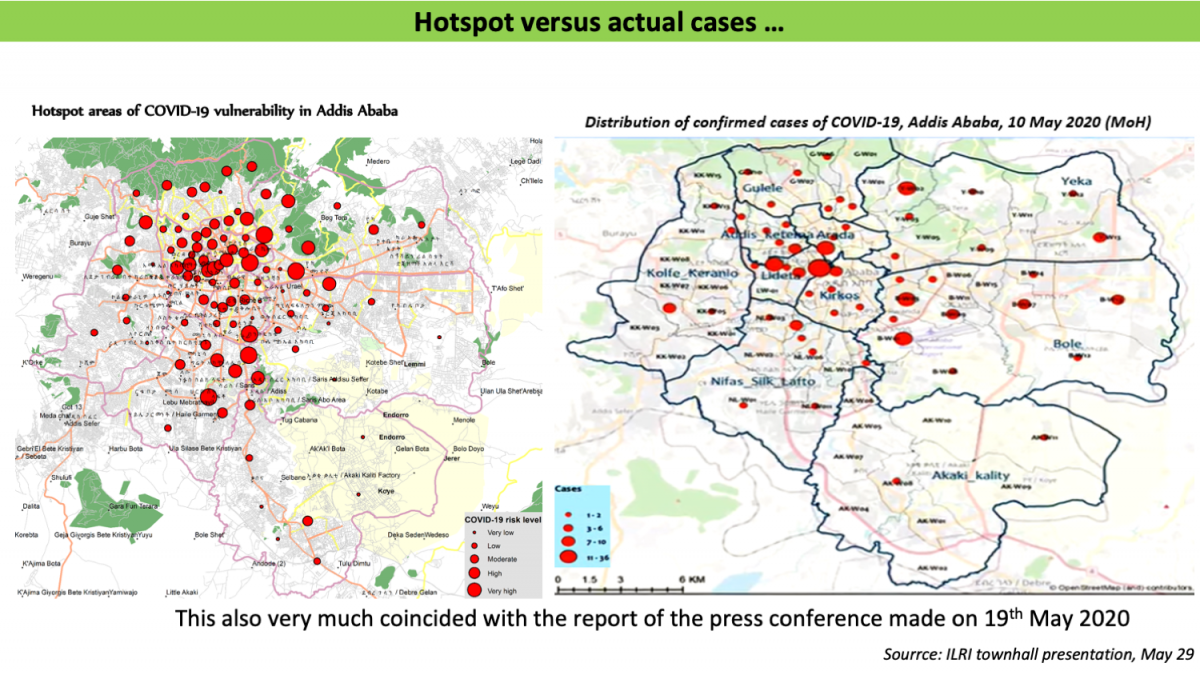

The team began by looking at hotspots. Addis was prioritized, given its large population and the number of people who had arrived in Addis from abroad. Based on some initial criteria related to such matters as physical distancing, livelihood status, means of livelihood, housing conditions, means of transport, and water access, the team created a hotspot map and presented it to the ministry of health. Despite the lack of good-quality data, the team was able to create reliable maps showing where outbreaks might occur and thus should be prioritized for intervention. To verify their analysis, they compared maps of actual cases with the mapped hotspots, which showed good agreement (see figures below).

The Ministry of Health suggested that the team be supported so as to obtain more granular data to improve the mapping and also to scale the work to the national level. Good-quality data at appropriate resolutions are needed to develop hotpot maps with useful detail. Ministry officials have provided further data that has helped to refine and upgrade the maps.

“Data are key to making sure we can provide evidence-based solutions,” said Tamene. “This spirit of collaboration with the Ethiopian government builds on our work over the last few years to formulate and implement solutions to data-sharing bottlenecks.”

Other maps and tools, including a dashboard to facilitate visualization and an app that will pinpoint where the mass sample testing should be carried out, are also being developed and made available to the ministry of health. “We wanted to support the ministry quickly and are pleased with the results and hope they will be useful for targeting interventions,” said Tamene.

“We very much appreciate the ILRI-Alliance team for their support in our fight against COVID-19. They were able to generate a hotspot map that aligns well with maps of real cases of COVID-19,” said Munir Kassa, a COVID-19 taskforce plan team leader in the ministry of health, after the scientific coalition presented its initial results.

The results from these two complementary activities were presented by the ILRI-AHRI-Alliance team in late April 2020 to the national taskforce to explore how the team could support the ministry of health in conducting mass testing in prioritized hotspot areas.

These activities involved experts from Addis Ababa City Administration Health Bureau, Addis Ababa University, AHRI, CIAT, EIAR, ILRI, MHE and WLRC, reflecting a truly interdisciplinary team of experts in action. An important lesson for the coalition of scientists is nicely summed up by Tadelle: ‘To win this fight, we have to work together and cross boundaries from agriculture to human health and build bridges across CGIAR.’