Bridging science and tradition to tackle zoonotic diseases in Isiolo County, Kenya

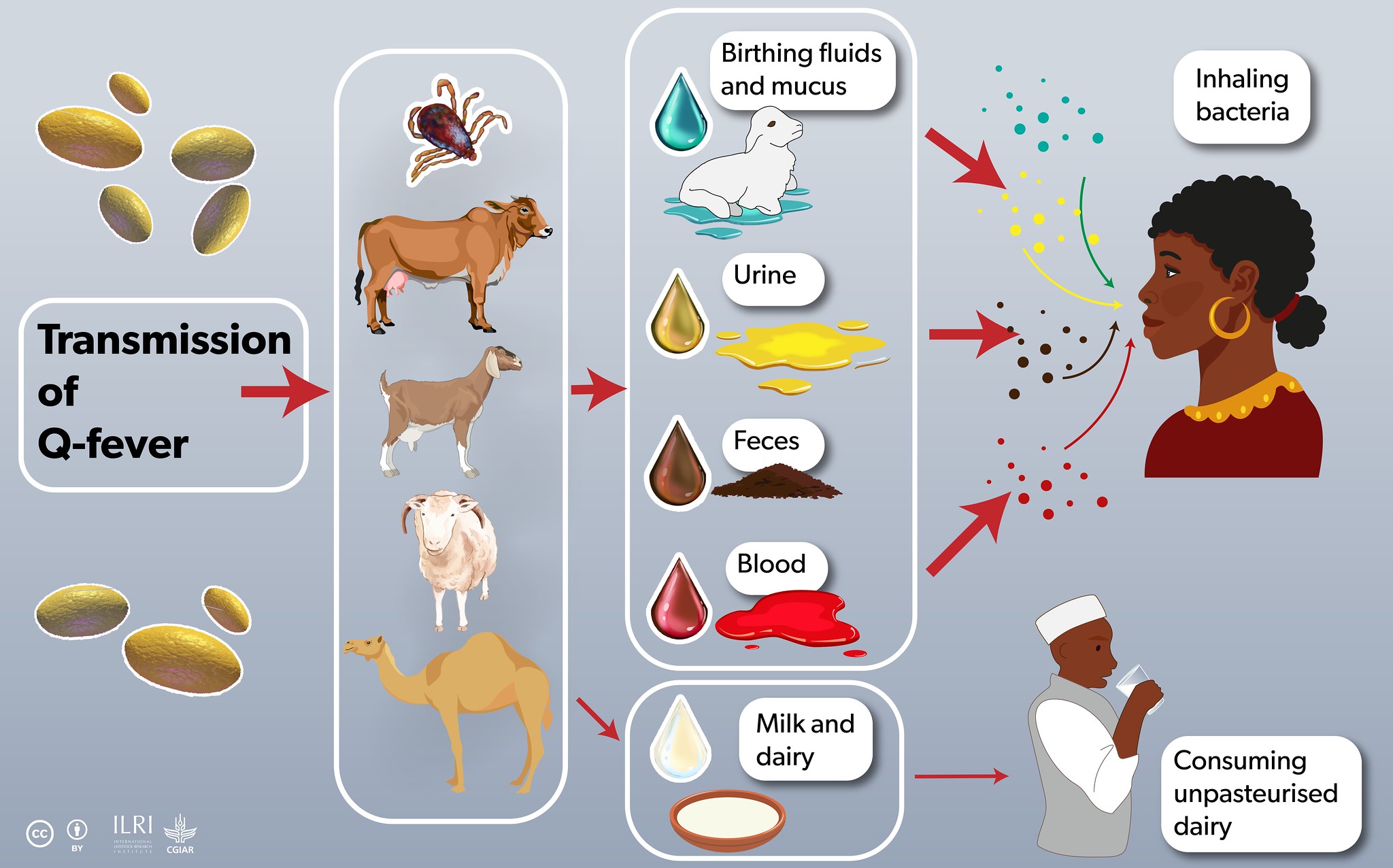

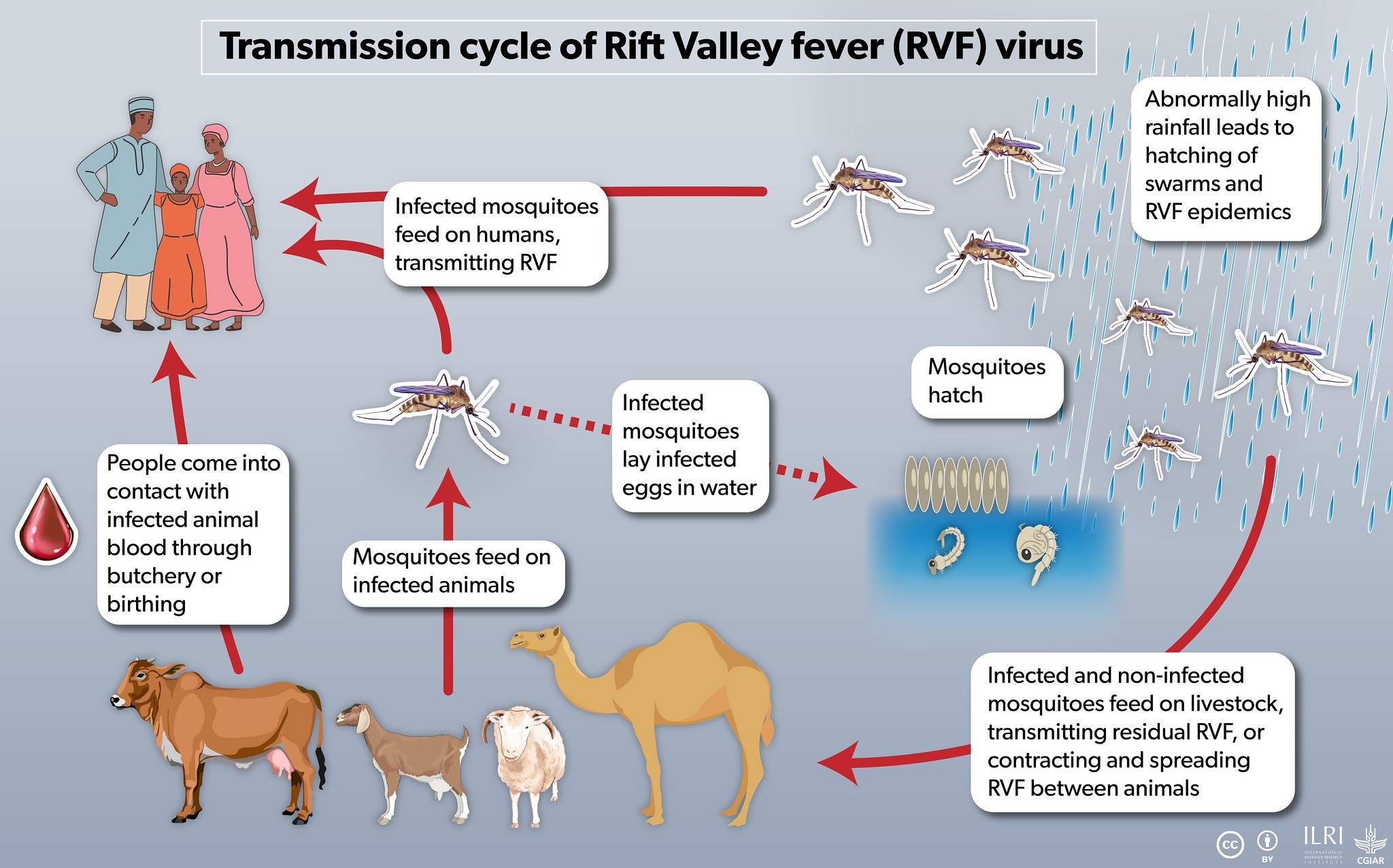

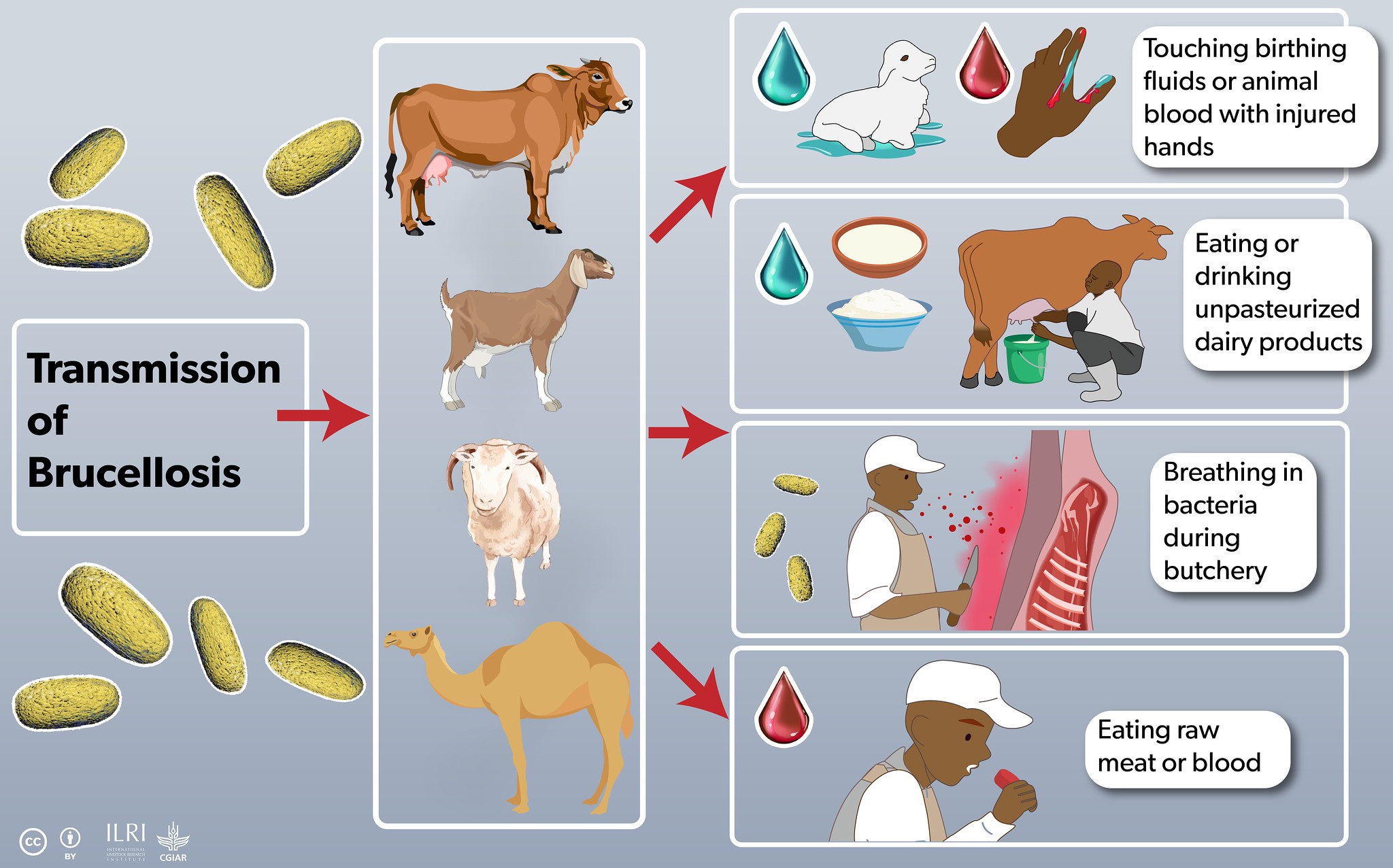

In rural pastoral areas like those in Isiolo County, people and their animals share a close bond, which sometimes facilitates the spread of zoonotic diseases which are transmitted from animals to humans. It was this close-knit coexistence of people and animals that gave rise to the Co-infection with Rift Valley fever virus, Brucella spp. and Coxiella burnetii in humans and animals in Kenya: Disease burden and ecological factors project. Initiated in Isiolo in 2021, this project aimed to uncover how diseases like brucellosis, Rift Valley fever and Q fever spread and persist in these communities.

The co-infection project employed a multidisciplinary team, with experts from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), national ministries of health and livestock, County Government of Isiolo, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kenya Wildlife Service and Washington State University, with the community at the centre of project implementation. From the inception meeting to progress gatherings, the team worked in collaboration with the community, always putting their perspectives at the forefront.

James Akoko, the co-infection project research coordinator, vividly remembers the enthusiasm of community members, a testament to the beneficial exchange of knowledge that took place. Community interaction was incorporated into the study by including community elders as guides and Borana-speaking study staff in the sampling to ensure open communication.

‘Our collective efforts fostered mutual learning, bridging the gap between scientific findings and the community’s rich knowledge,’ remarks Akoko, highlighting the symbiotic relationship fostered over the past year.

A progress meeting with community members in Kinna Ward, Isiolo, Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/James Akoko).

For a year, researchers monitored 140 households and their livestock, with individuals and animals undergoing quarterly blood tests to assess exposure to the three targeted pathogens and observe related syndromes. The findings would offer control options and identify barriers to implementing these controls.

During the progress meetings, the team engaged in open dialogue with the community, discussing objectives and integrating their feedback. Two sessions occurred on 1–2 September 2023, in Kinna and Rapsu locations in Isiolo County. A team from ILRI and the Kenya Zoonotic Disease Unit, together with the Isiolo County disease surveillance coordinator, the Garbatulla sub-county focal person for zoonotic disease and a representative from the Isiolo County Veterinary Department facilitated the discussions.

Community feedback session in Kinna Ward, Isiolo, Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/ Diba Tasi).

Zoonotic disease awareness

The study revealed that consuming raw milk, aiding in livestock births, handling aborted tissues, slaughtering and butchering of animals, and having at least one infected animal in a herd increased the risk of exposure to Brucella and other zoonotic diseases. Animals with abortion histories or retained placentas showed higher brucellosis likelihood. Cattle, sheep, goats and camels could all potentially expose humans to brucellosis.

To address these issues, the project team emphasized zoonotic disease awareness and control measures. These included boiling raw milk, disposing aborted tissues properly, and using protective gear during livestock deliveries, given that lack of personal protective equipment when handling products of conception was one of the biggest challenges observed.

Myths versus facts

The community identified key obstacles to controlling zoonotic diseases such as brucellosis and the scientists introduced research-based facts to foster a healthier community.

Myth: Drinking raw milk is a cultural norm. Boiling milk not only curses the animals, reducing their milk production, but also diminishes the milk’s nutritional value.

Fact: Boiling milk aims to eliminate harmful pathogens. It does not affect the animals’ milk production or significantly degrade the milk’s nutritional value.

Myth: In the Borana culture, the primary treatment for human brucellosis is a two-week massage by a traditional healer. After this, the patient becomes a healer, ready to treat other patients suffering from brucellosis.

Fact: While traditional practices are deeply rooted in culture, scientific research advocates for tests, followed by medical treatment using antibiotics as the recognized and effective methods to treat brucellosis.

Myth: If one avoids meat or milk for more than 40 days, especially during the 6–8 week treatment for brucellosis, they risk severe health consequences, even rabies.

Fact: The medical recommendation to avoid certain foods during treatment is based on optimal recovery. There is no scientific evidence linking abstention from meat to developing rabies or other health issues.

Myth: Feeding aborted tissues and placenta to dogs is better than burial because dogs will dig them up anyway.

Fact: Proper disposal methods, beyond mere burial, are essential in preventing the spread of diseases. Such practices ensure that pathogens are contained and do not pose risks to other animals or humans.

Such myths sow confusion and fear and hinder control efforts for brucellosis and other endemic zoonoses. They inadvertently amplify the risk of diseases, negatively impacting pastoral settings like Isiolo. A combined and regular effort from social scientists, medical experts, community health workers and local leaders is needed to not only control diseases but also safeguard the future of pastoral communities.

Partners of the project include the Kenya Wildlife Service, Wildlife Research and Training Institute, Washington State University, University of Nairobi, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Los Alamos National Laboratory in the US, and the Zoonotic Disease Unit.

The ILRI-led project ‘Co-infection with Rift Valley fever virus, Brucella spp. and Coxiella burnetii in humans and animals in Kenya: Disease burden and ecological factors,’ is sponsored by the United States Defence Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA). The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the federal government and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Additional information

Infographics by a.slater@cgiar.org, available for download on Flickr

You may also like

Related Publications

Rift Valley fever virus remains infectious in milk stored in a wide range of temperatures

- Dawes, B.E.

- De La Mota-Peynado, A.

- Rezende, I.M.

- Buyukcangaz, E.K.

- Harvey, A.M.

- Gerken, Keli N.

- Winter, C.A.

- Bayrau, B.

- Mitzel, D.N.

- Waggoner, J.J.

- Pinsky, B.A.

- Wilson, W.C.

- LaBeaud, A.D.

Rift Valley fever epidemiology: shifting the paradigm and rethinking research priorities

- Rostal, M.K.

- Thompson, P.N.

- Anyamba, A.

- Bett, Bernard K.

- Cêtre-Sossah, C.

- Chevalier, V.

- Guarido, M.

- Karesh, W.B.

- Kemp, A.

- LaBeaud, A.D.

- Lubisi, A.

- Matthews, L.

- Msimang, V.

- Njenga, M.K.

- Ross, N.

- Tumusiime, D.

- Wilson, W.C.

- Weyer, J.

- Paweska, J.T.

- Swanepoel, R.

Machine learning approach to predicting Rift Valley fever disease outbreaks in Kenya

- Mulwa, D.

- Kazuzuru, B.

- Misinzo, G.

- Bett, Bernard K.

Spatial and temporal analysis of Rift Valley fever outbreaks in livestock in Uganda: a retrospective study from 2013 to 2022

- Arinaitwe, E.

- Atuhaire, D.K.

- Hasahya, Emmanuel

- Nakanjako, G.K.

- Mwebe, R.

- Nizeyimana, G.

- Afayoa, M.

- Mwiine, F.N.

- Erume, J.