Winning, ‘climate-smart’, ways to feed India’s dairy cows—Jimmy Smith, of ILRI

(The post was written by Kennady Vijayalakshmy, research and communications officer with ILRI in South Asia, with additional editing by Susan MacMillan, ILRI emeritus fellow)

Jimmy Smith, director general of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), spoke this week (27 May 2021) at the 8th Research Advisory Committee meeting of India’s National Dairy Development Board.

Smith’s slide presentation focused on India’s fast-rising demand for dairy products, the dominance of smallholders in the country’s dairy sector, and the smart (and ‘climate-smart’) dairy feeds that will be needed to grow India’s dairy sector.

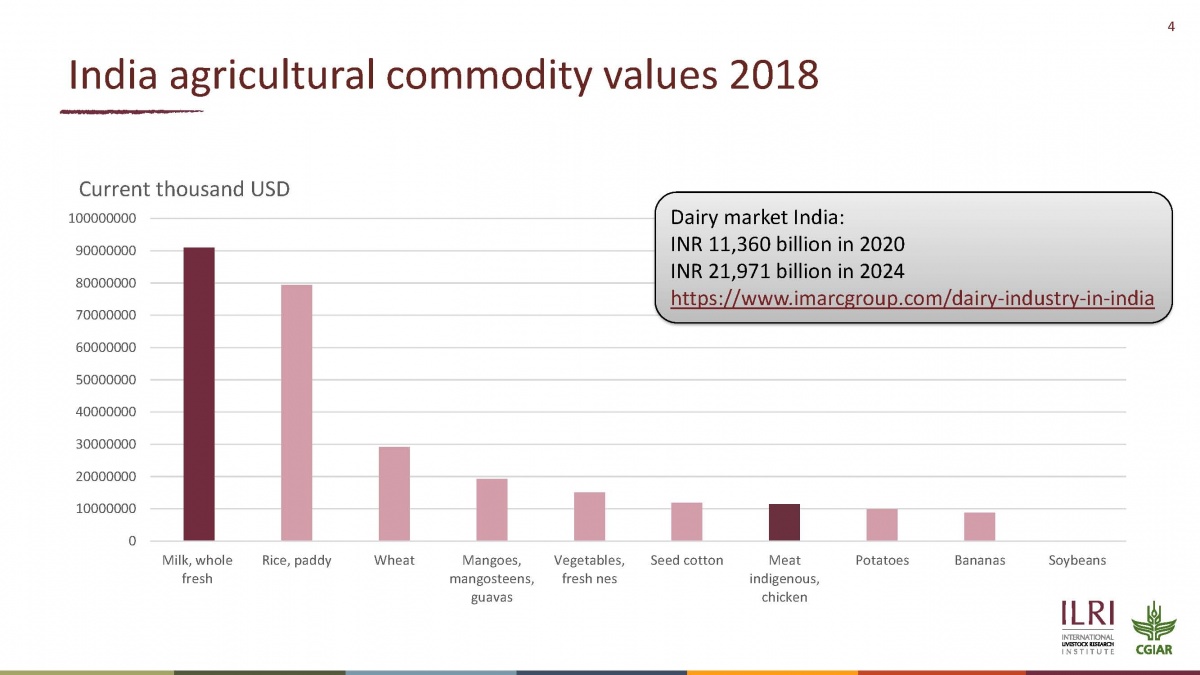

The commodity value of India’s dairy market, Smith said, is high—it was around 11,360 billion Indian rupees (INR) in 2020 and is predicted to almost double—to around INR21,971 billion—by the year 2024.

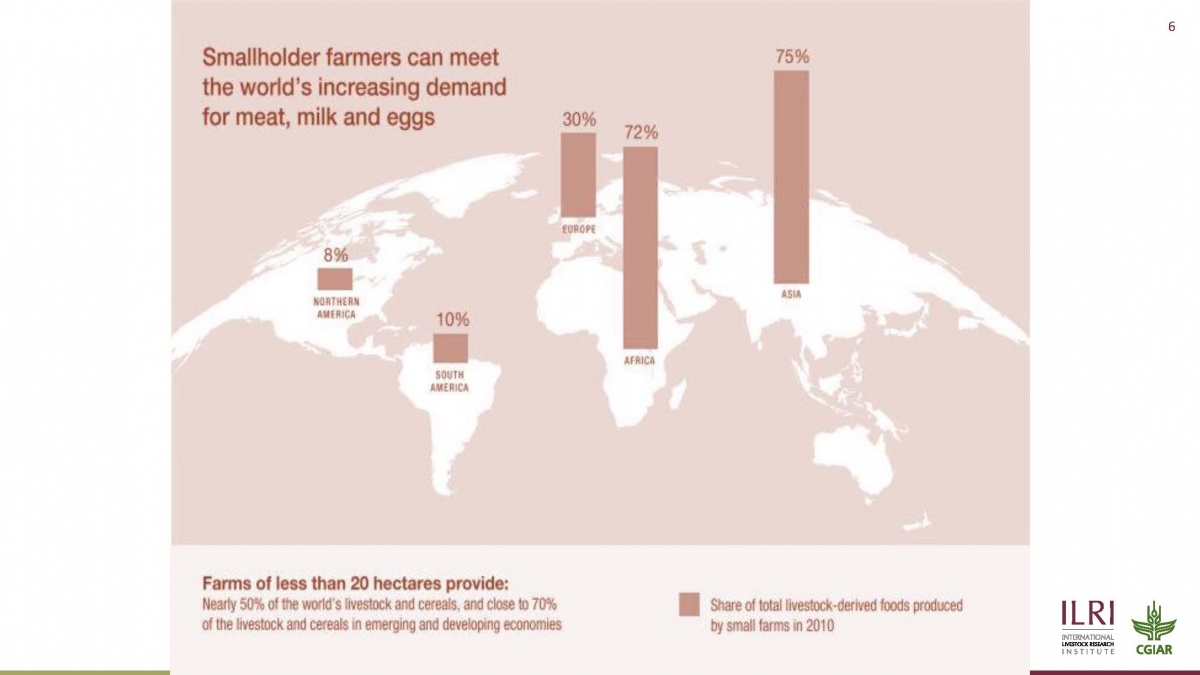

While most of the dairy farms in India keep fewer than ten animals, Smith argued that these small-scale producers are big producers in aggregate. Farmers on less than 20 hectares of marginal and other land, he said, produce nearly 50% of the world’s livestock and cereal products globally, a percentage that rises to almost 70% in the world’s developing and emerging economies.

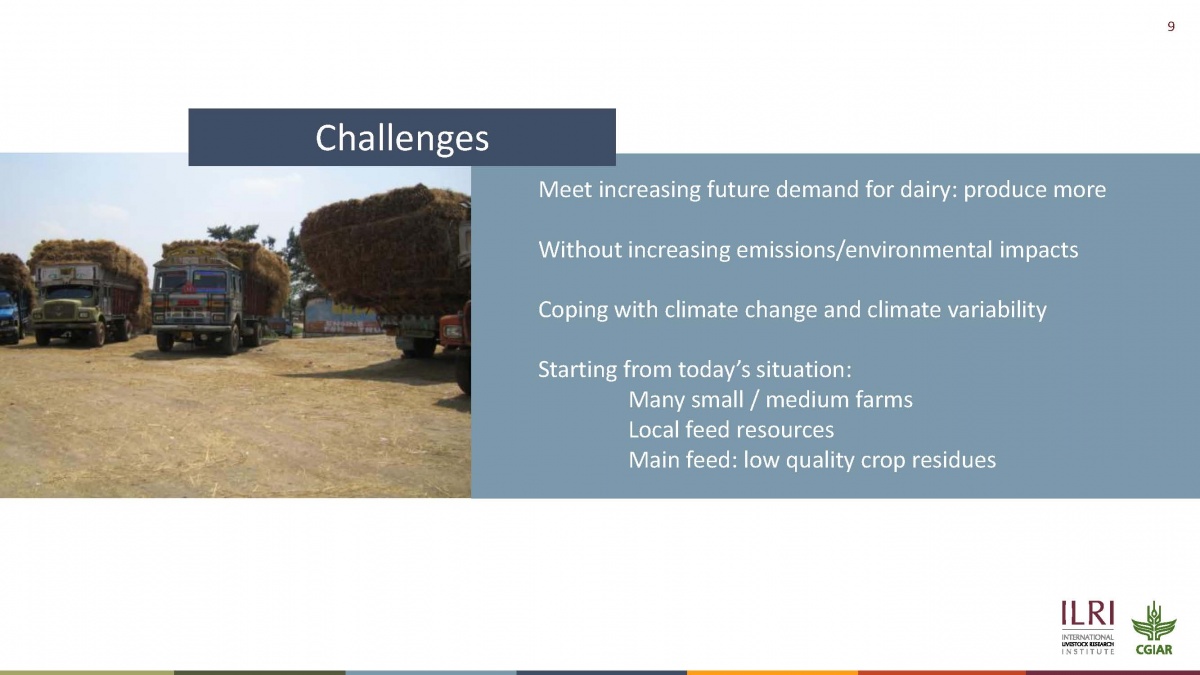

Most of South Asia’s dairy feeds (60%) consist of ‘stover’—the stalks, stems, leaves, pods and other components of cereals and legumes that remain after their grain or pulses have been harvested for human consumption. As the country’s dairy production increases, so will its requirement for greater amounts of such ‘crop residues’ for feeding these cows. And these increases must be achieved, first, in the face of an increasingly erratic and changing climate and, second, without increasing the greenhouse gases emitted by the dairy sector.

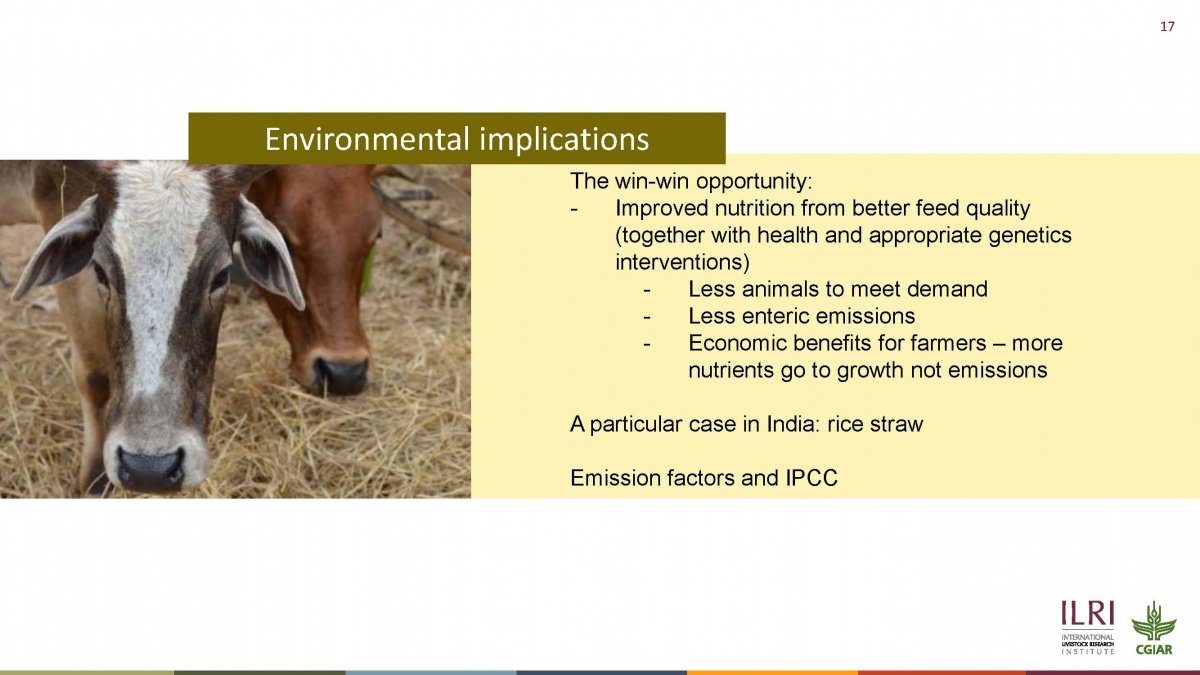

ILRI and India research shows that small changes in crop residue quality have a significant impact on milk production. Just a 1% increase in digestibility of sorghum stover fed to dairy cows, for example, leads to a 6–8% increase in milk production.

Better feed options, Smith said, will come about with selection of better quality feed. This is being achieved, Smith said, by including parameters of animal feed quality in programs breeding and selecting food crop varieties—and demonstrating that selecting varieties with higher feed quality and quantity does not harm their grain yield quality or quantity.

To be successful, this dual, ‘feed plus food’, selection of crop varieties needs quick and easy ways for the country’s crop breeding and selection programs to assess the feed quality of different crop varieties. That is achieved by use of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), which can quickly and accurately assess feed quality parameters and predict feed traits in plant breeding programs. This impressive technique obviates the need to conduct any feeding trials to determine the feed quality of different crop stovers.

Also needed for supplying India’s growing dairy sector with greater dairy feed is to improve feed utilization through processing. This can be achieved by manufacturing ‘densified’, supplemented and balanced feed blocks. ILRI has tested, with India’s commercial dairy buffalo farmers, feed blocks with higher (52%) and lower (47%) digestible sorghum stover. The milk yields of the buffalo cows was found to be around 15.5kg/day and 9.9 kg/day, respectively.

Another use of processing methods to improve feed utilization by dairy animals can be achieved by leveraging spin-offs from second-generation biofuel technologies to upgrade lignocellulosic biomass for animal feeding. This has been tested using a ‘2 Chemical Combination Treatment (2CCT)’ developed by ILRI with the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)–Indian Institute of Chemical Technology (IICT).

The total enteric methane emissions from Indian livestock is around 9.253 Tg/year (1 Tg=1 million metric tonnes), with cattle contributing more than half (56%) of this potent greenhouse gas. A 2018 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Global Dairy Platform says a ‘win-win’ is possible. It estimates that a doubling of milk yield through better feeding in India could also cut the country’s total methane emissions by 25%.

But Smith stressed that India needs to find ways for farmers to adapt to, as well as mitigate, climate change. ‘Climate change has deleterious impacts on livestock. This includes heat stress that directly reduces livestock yields. A rise in temperature and greater climate variability can also reduce forage and pasture yields, increase the risk of livestock diseases due to an expansion of the geographical range of vectors of livestock pathogens, and can change the kinds of livestock production systems that remain viable.’

In a discussion following Jimmy Smith’s presentation, J B Prajapathi, principal and dean of the Sheth M C College of Dairy Science, in Anand, Gujarat, expressed interest in programs to train farmers about the importance of methane emissions from their livestock. Prajapathi asked whether any study had been conducted on including probiotic supplements in animal feed to reduce enteric methane emissions from livestock. Smith mentioned several promising recent studies on the use of seaweed for animal feed, which appears to reduce methane from cattle. Habibar Rahman, ILRI’s regional representative for South Asia, further said that under an ILRI-Indian Council of Agricultural Research collaborative project on methane emissions and mitigation, a feed supplement called ‘Harit Dhara’ has been developed, which is found to significantly reduce enteric methane emissions from cattle, buffalo and sheep.

View the whole presentation by Jimmy Smith here: ‘Winning solutions for climate-smart dairy animal nutrition in India’.