FAO conference on livestock transformation: Mounir Louhaichi says 'It's not the cow; it's the how'

Landmark UN conferences in Rome and Dubai are putting sustainable livestock issues in the limelight

At this year’s ongoing climate summit, in Dubai, livestock issues are being defined by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and its partners as a climate change ‘solution with legs’. The high profile of livestock and other food systems issues at this year’s climate summit, the 28th such annual event, is a first. This milestone was enhanced two months earlier by a global livestock conference hosted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), where 740 livestock experts—of all kinds and representing livestock systems of all kinds practiced in all parts of the world—gathered in Rome for a Global Conference on Sustainable Livestock Transformation. The agenda of the conference, the first of its kind ever held by FAO, was organized thematically around the Four Betters of FAO’s 2021 strategic framework: Better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life.

The FAO conference

Among the delegations participating in the FAO Rome meeting was one from ILRI. Mounir Louhaichi, a rangelands scientist at ILRI’s sister centre, the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), spoke on 'Balancing livestock production and the sustainability of natural resources' on behalf of the CGIAR Initiative on Livestock and Climate, which is led by ILRI. (You can view Louhaichi’s presentation here and you can watch it here: his 14-minute presentation starts at 1:37:49 minutes and ends at 1:51:55 minutes.)

Louhaichi started with some ‘quick facts’, some of them contrary to popular beliefs.

Climate-smart livestock and livestock-smart grazing

Louhaichi argued that livestock are a ‘climate solution’—due in part to their ability to convert vegetation inedible by humans into nutrient-rich foods for people and also to their ability to support healthy soils and lands with prudent livestock grazing.

Alarm bells

In spite of this, he went on to say that both underinvestment and degradation continue to characterize much of the world’s livestock sector.

‘Our natural resources continue to degrade. We need to do something about it. Our challenge is to make livestock production sustainable.’

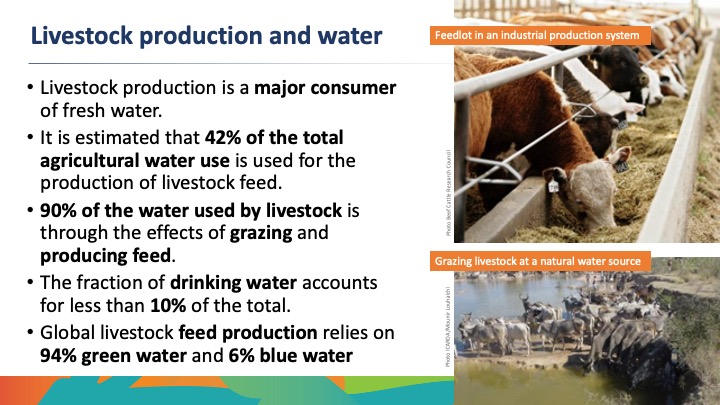

Louhaichi proceeded to provide some examples of livestock’s use of natural resources, starting with a few (surprising) facts about water use by livestock.

While agreeing that livestock is a major consumer of water, he noted that most of that water is used to grow feed for livestock, of which 94% is ‘green water’ (e.g. rainfall that falls regardless of its use) rather than ‘blue water’ (e.g. surface water found in lakes and rivers).

Similarly, he said, livestock can affect soils both positively and negatively. Livestock manure, for example, is a serious problem in some developed countries but is a benefit in developing countries, where it helps to enrich soils through the nitrogen and organic matter it provides.

‘When we hear about degraded rangelands, the first thing that goes through our minds is livestock overgrazing. But who is responsible for this overgrazing? After all, cattle and other ruminant livestock are herded by humans. So it’s up to us to change this.’

And while it’s true that livestock herding can compact soils, he said, it’s also true that their hooves can break that compaction, improving water and mineral cycling.

A disaster foretold

Louhaichi then turned to (unsustainable) land-use change—from pasture to plot, the impact of which is enormous on both the environment and livestock herding.

‘The mono-cropping of barley in the drylands of the Middle East, year after year, is leading not just to degradation but also to desertification. This situation is getting worse and worse.’

The great rebuild

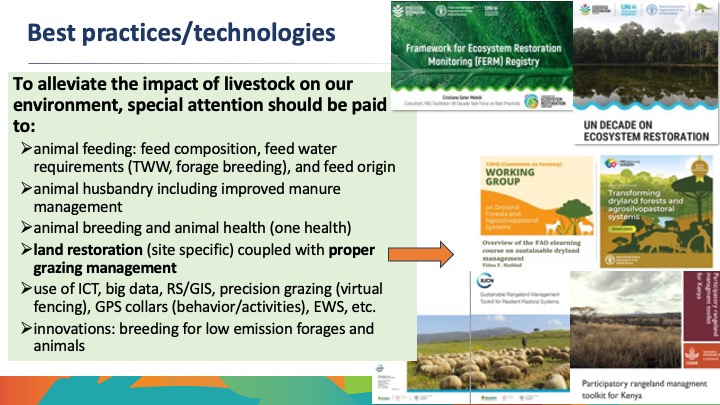

Louhaichi argued that we have many best practices, technologies, and tools with which to find and exploit livestock ecosystem wins. Proper livestock grazing, he said, can be an effective management tool, while unbalanced grazing, whether undergrazing or overgrazing, harms rangelands by impoverishing soils, by encouraging the encroachment of shrubs and invasive species, and by reducing biodiversity.

Much can be accomplished, he argued, by engaging and supporting local livestock herders in managing their rangelands.

Participatory rangeland management is one way to restore degraded lands. It takes time to build trust with local communities. But we don’t have a choice. If our natural rangelands continue to degrade, the cost of inaction will be very, very high.’

It’s not the cow; it’s the ‘how’

Where do we stand now? Louhaichi asked.

‘We need integrated and balanced approaches. We need to change our behaviors. As the saying goes, It’s not the cow, it’s the how.’

We need better policies, he said, citing bans on cropping fragile rangelands. And more research and innovation. And deeper investments if we’re going to revive rather than deplete our invaluable, and imperiled, rangeland resources.

Protecting the guardians of half the Earth

In conclusion, Louhaichi reminded his audience that the United Nations declared 2024 to be the International Year of Camelids. In 2026, he said, ‘we’ll celebrate the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists.’

'A major way to do that is to help reverse the dire conditions threatening the world’s rangelands, peoples and animals.'

You may also like

ILRI News

ILRI presents results of Livestock Sector Analysis and Strategy for Nigeria: Major step towards a national livestock master plan

ILRI News

Veterinary conference challenges experts to adopt new approaches to livestock development in India

Exploring integration of KAZNET into Ethiopia’s national and regional resilience programming and information systems

Related Publications

Context Matters: Tackling Methane in Livestock Systems for a Sustainable Future

- Food Systems for the Future (FSF)

- Environmental Defense Fund

- International Livestock Research Institute

Livestock farmer groups for innovation uptake, market access and policy influence in Mai Son District, Son La Province, Vietnam

- Thinh, Nguyen Thi

- Thanh, Lo Quang

- Le, Pham Thi

- Marshall, Karen

- Atieno, Mary

- Burkart, Stefan

One Health scientific conference: International practices and lessons learned for Vietnam

- Vietnam One Health Partnership

- International Livestock Research Institute

Policy levers to unlock climate finance in the livestock sector: A guide for national policymakers to integrate livestock in climate strategies

- Alemayehu, Sintayehu

- Cramer, Laura K.

- Gonzalez Quintero, Ricardo

- Kimoro, Bernard

- Kohler, Gregory

Proceedings of the First Technical Advisory Steering Committee Meeting for ‘Strengthening Adaptive Capacity of Extensive Livestock Systems for Food and Nutrition Security and Low-emissions Development in Eastern and Southern Africa’ Project in Ethiopia

- Mekuriaw, Shigdaf

- Dijk, Suzanne van

- Makonnen, Brook T.