Filling in the blanks for carbon and water cycling in East African drylands

New science

Posted on

Contributors

Dryland ecosystems cover large parts of East Africa, yet we still know surprisingly little about how they exchange carbon and water with the atmosphere over the course of a season. This is because direct, ecosystem-scale measurements from these environments are rare. As a result, even basic questions about when drylands take up carbon, when they release it, and how this links to rainfall remain only partly answered.

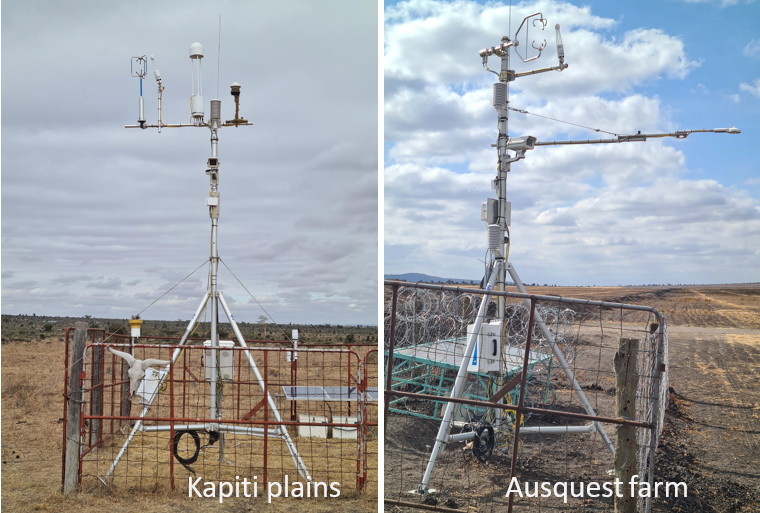

A recent study set out to collect vital data on these processes by monitoring a semi-arid rangeland and a neighboring rain-fed cropland in southern Kenya using the Eddy Covariance technique (Figure 1). Eddy covariance is a field-based measurement to track how much carbon dioxide (CO2) and water vapour move between the land surface and the atmosphere.

The two sites experience the same climate and soils but differ in vegetation and land use. The scientists observed them side by side through one growing season and the following dry-down.

Different rhythms, similar results

Over the observation period, both ecosystems exchanged similar amounts of carbon overall, but they did so in very different ways. In the rangeland, carbon exchange rose and fell closely with rainfall. During dry periods, the ecosystem tended to release carbon, while rainfall events triggered brief periods of uptake. This pattern reflects a system that is strongly shaped by water availability and able to respond quickly when moisture becomes available, even if those opportunities are short-lived.

The cropland followed a different dynamic. Carbon uptake increased as crops emerged and grew, reaching its highest levels during the middle of the growing season. Once the crops matured and were harvested, carbon uptake ceased and the ecosystem started to emit carbon.

In addition to rainfall responses of carbon uptake and release, the researchers also considered the total carbon budget over the observation period. In the rangeland, the balance of carbon uptake (during wet periods) and release (during dry periods) was close to zero, that means the rangeland was carbon neutral in its CO2 balance. The cropland took up more carbon during the wet period than what was released during the dry period, which means it was a temporary carbon sink. However, when the carbon removed in harvested grain was taken into account (the so-called “lateral carbon transfer”), much of this apparent seasonal carbon uptake was offset. In other words, the cropland temporarily stored carbon during growth, but a large share of that carbon was later exported out of the system, which also made the cropland carbon neutral. These carbon balances do not represent a full GHG budget however as only CO2 balance is measured, and not other greenhouse gases.

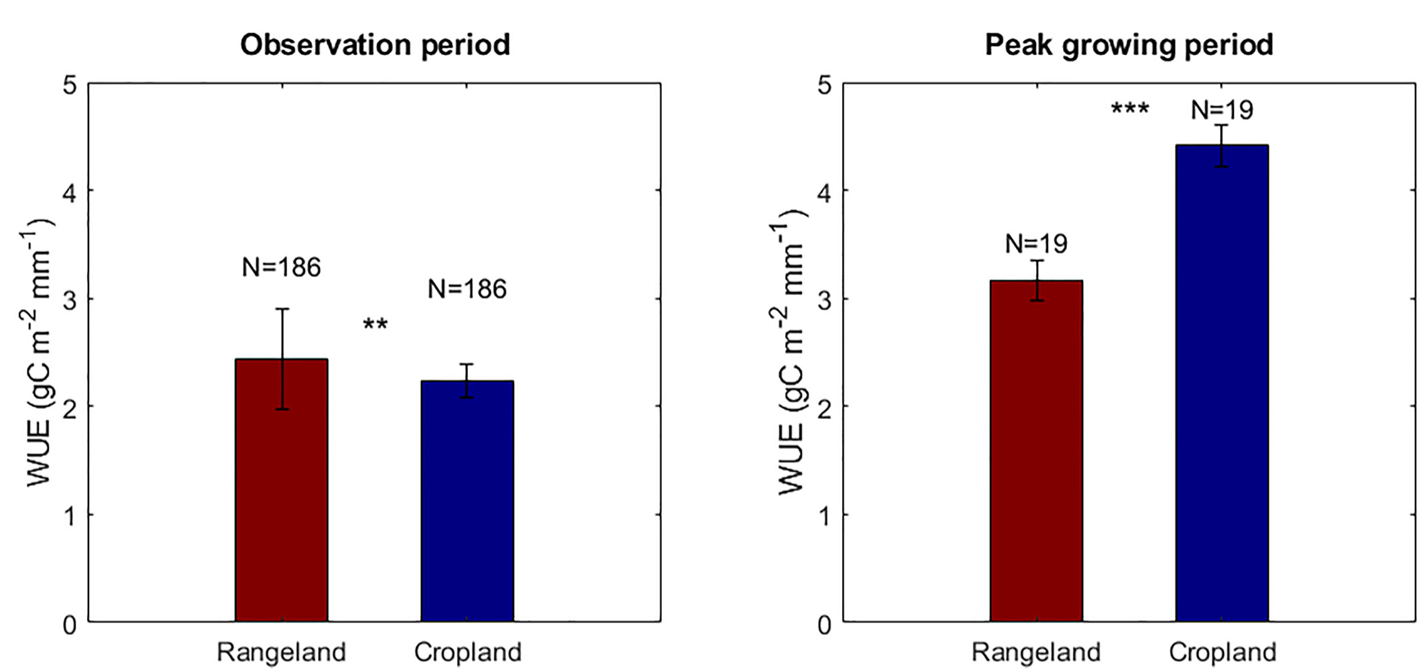

Efficiency vs. consistency: the water story

Water use (Figure 3) also followed contrasting patterns. During the peak growing period, the cropland used water more efficiently than the rangeland, meaning it converted rainfall into plant growth very effectively over a short time period. After harvest, when vegetation was absent and the soil was bare, water use in the cropland was zero because there were no plants taking up water and CO2. When considering this and calculating water use efficiency across the full observation period, the rangeland showed more consistent water use because it had a continuous vegetation cover that remained active beyond the main growing phase. These differences illustrate how the timing of vegetation activity, rather than total rainfall alone, shapes how dryland ecosystems function.

The big picture

One of the clearest lessons from this comparison is that similar seasonal carbon balances can arise from very different internal dynamics. Whether an ecosystem gains or loses carbon depends strongly on when rain falls, how long vegetation remains active, and whether carbon is retained locally or removed through harvest. Focusing only on periods of high productivity can therefore give a misleading picture of how dryland systems operate as a whole.

The study does not describe long-term trends or future behaviour, but it does document how two dryland land-use types common to sub-Saharan Africa behave over a single, shared climatic period. By following both systems through wet and dry phases, it shows how quickly carbon and water exchanges can shift within a season, and how strongly these shifts depend on land use and vegetation dynamics.

Why local data matter

Such observations are essential for building a more realistic understanding of dryland ecosystems. Before broad claims are made about carbon storage or climate mitigation in these landscapes, it is necessary to first understand how carbon and water actually move through them on the timescales that matter most to plants, soils, and microbes. This study offers one such piece of evidence, grounded in direct measurement and careful comparison, from a region where such data remain scarce.

About the study

The study was led by Vincent Odongo and Sonja Leitner of the Mazingira Centre at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Kenya, together with Lutz Merbold of Agroscope in Switzerland. The research team included collaborators from King’s College London (UK), Lund University (Sweden), the Natural Resources Institute Finland, and the University of Auckland (New Zealand), bringing together experts in ecology, atmospheric science, remote sensing, and agricultural management. The findings were recently published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, a peer-reviewed journal focusing on ecosystem processes and climate science.

Here's the link to the full paper: https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JG008623

The study was part of the project ESSA - Earth observation and environmental sensing for climate-smart sustainable agropastoral ecosystem transformation in East Africa.

You may also like

ILRI News

Africa–Asia Bioscience Challenge Fund: Building the next generation of bioscience leaders for climate-resilient livestock systems

Opinion and analysis

Sustainable manure management in Uganda requires an enabling policy and legal framework: a call to action!

ILRI News

ILRI introduces the Livestock and Climate Solutions Hub at SAADC 2025 to address climate challenges in livestock systems

Related Publications

Systematic review on the impacts of community-based sheep breeding programs on animal productivity, food security, women’s empowerment, and identification of interventions for climate-smart systems under the extensive production system in Ethiopia

- Tesfa, Assemu

- Taye, Mengistie

- Haile, Aynalem

- Nigussie, Zerihun

- Najjar, Dina

- Mekuriaw, Shigdaf

- Dijk, Suzanne V

- Wassie, Shimels E

- Wilkes, Andreas

- Solomon, Dawit

The impact of heat stress on growth and resilience phenotypes of sheep raised in a semi-arid environment of sub-Saharan Africa

- Oyieng, Edwin P.

- Ojango, Julie M.K.

- Gauly, M.

- Ekine-Dzivenu, Chinyere C.

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Clark, E.L.

- Dooso, Richard

- König, S.

Genetic relationships among resilience, fertility and milk production traits in crossbred dairy cows performing in sub-Saharan Africa

- Oloo, Richard Dooso

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Ekine-Dzivenu, Chinyere C.

- Ojango, Julie M.K.

- Bennewitz, J.

- Gebreyohanes, Gebregziabher

- Okeyo Mwai, Ally

- Chagunda, M.G.G.

Ambient environmental conditions and active outdoor play in the context of climate change: A systematic review and meta-synthesis

- Lee, E.-Y.

- Park, S.

- Kim, Y.-B.

- Liu, H.

- Mistry, P.

- Nguyen, K.

- Oh, Y.

- James, M.E.

- Lam, Steven

- Lannoy, L. de

- Larouche, R.

- Manyanga, T.

- Morrison, S.A.

- Prince, S.A.

- Ross-White, A.

- Vanderloo, L.M.

- Wachira, L.-J.

- Tremblay, M.S.