Feedlot feeding improves beef productivity and lowers methane intensity in Tanzania

Scientists have found strong evidence that improved feeding systems, specifically feedlotting with local concentrate feeds, are an effective and immediate ways to reduce methane intensity in East African pastoral livestock systems, while increasing productivity.

Moving cattle from grazing-only systems to these feedlot systems substantially improved weight gain and reduce methane emissions per kilogram of meat produced, found researchers from Tanzania’s Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Aarhus University, and International Livestock Research Institute's (ILRI) Mazingira Centre.

“Feed quality and feeding systems are powerful levers for both productivity and climate goals,” said Claudia Arndt, corresponding author and team leader of Mazingira Centre.

Tanzania’s beef challenge

Tanzania’s cattle sector is central to rural livelihoods, providing income, nutrition, and draft power for millions of households. Despite having one of Africa's largest cattle populations, most animals are raised in traditional pastoral systems dependent on natural grazing, where forage quality fluctuates seasonally, and animal growth rates can be low.

These conditions slow growth to market weight and cause animals to emit more methane per kilogram of weight gain.

At the same time, Tanzania’s growing population and rising incomes are driving up meat demand, creating pressure to produce more beef from the same land base while keeping emissions low.

A promising solution: feedlot systems with concentrate supplementation

To find out how local farmers can feed animals better and affordably, researchers carried out a controlled feeding experiment at Kongwa Ranch in central Tanzania.

They compared two popular cattle breeds, the indigenous Tanzanian Shorthorn Zebu and the regional crossbreed Boran, under three feeding systems: pure grazing, combined grazing and feedlot feeding, and full feedlot feeding with varying levels of concentrate supplementation.

Feedlotting allows animals to be fed balanced rations rich in energy and protein, improving digestibility and growth efficiency. The higher the proportion of concentrate, the greater the nutrient intake, and the lower the methane produced per kilogram of weight gained (known as the methane intensity).

The concentrate mix was based on locally available ingredients - maize meal, cottonseed cake, molasses, mineral mix, salt, and urea - and provided about 12.5% protein per kilogram of dry matter.

Measuring performance and emissions

The researchers measured daily feed intake, weight gain, and estimated methane emissions using the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2019 guidelines.

Methane intensity was used to assess production efficiency and environmental impact.

Feedlotting boosts growth

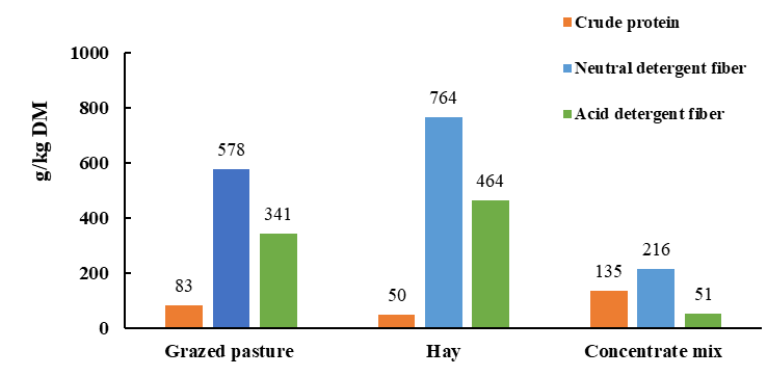

Feedlot diets provided more crude protein and lower fiber content than hay or natural grazing. For instance, crude protein content in hay is about 5%, while in the concentrate mix it is 13.5%. These improvements increased feed digestibility and energy availability for the animal, driving both higher growth rates and lower methane emissions per unit of output.

Cattle in feedlot systems gained weight 24–45% faster than those grazing only. Although Boran cattle emitted slightly more methane emissions per day (127 vs 114g CH4/day) due to their larger body size (168 vs 99 kg), they also grew faster (738 vs 626 g/day), which balanced overall efficiency.

Boran and the Tanzanian Shorthorn Zebu responded strongly to supplementation, showing that feedlot interventions can benefit both local and crossbred animals.

This suggests that feed improvement can benefit both breeds, making it relevant across pastoral and ranching systems in Tanzania.

Feedlot feeding reduced reduced methane emissions per kg of meat produced

Introducing feedlot feeding with concentrate supplementation reduced total methane production per day by 28–65% and cut methane per product by nearly 80% compared to grazing only cattle.

These results demonstrate that strategic feedlot feeding can simultaneously increase productivity and reduce methane intensity, offering a practical, climate-smart pathway for Tanzania's beef sector.

Why it matters

“Improving feeding systems is not just about faster growth—it is a cornerstone for emission mitigation and food security,” emphasized Arndt.

When animals grow faster under feedlot conditions, they spend fewer days emitting methane, resulting into more beef with overall fewer emissions.

This aligns directly with Tanzania’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and global goals for low-emission, climate-resilient livestock development.

From experiment to action

The study highlights a key opportunity for policymakers and producers: adopting feedlot systems that use affordable, locally available feed ingredients can deliver tangible productivity and climate benefits.

However, the researchers caution that scaling feedlot interventions requires attention to costs, feed supply chains, and farmer access to inputs such as crop by-products.

What’s next

In this study, methane emissions were estimated using IPCC (2019) equations. The next step is to measure methane directly under real-world farming conditions using individual animal methane measurements and drone-based measurements of groups of animals, recently developed at ILRI’s Mazingira Centre, to verify whether the estimated emissions accurately reflect field conditions.

Researchers will also evaluate feedlot and other feeding strategies to determine their effectiveness across different production systems and seasons.

Acknowledgements

The researchers acknowledge that funding support came from the CGIAR Initiatives Mitigate+: Research for Low Emissions Food Systems, Livestock and Climate, and the CGIAR Science Programs on Sustainable Animal and Aquatic Foods, Climate Action, and Multifunctional Landscapes. Additional support was provided by the EU-DeSIRA ESSA Project, DANIDA-ENRECA IGMAFU Project, Tanzania National Ranching Company (NARCO), and the New Zealand Government through the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases.