The G-FEAST journey in Madagascar: Building resilient feed systems through local voices

In Madagascar, the Gendered Feed Assessment Tool (G-FEAST) offered a fresh way to work with local institutions and farmers. We did not begin with a checklist of interventions; we began with questions: What if livestock systems could be transformed with better feeds? What if farmers themselves co-designed feed solutions, instead of having them designed from the outside?

Why better feed matters

Across Madagascar’s vast rural landscapes, livestock farming is practiced by about 71% of households and many families depend on livestock for milk, meat, draft power, and even savings. Cattle, pigs, poultry, and goats represent school fees, financial security, resilience and nutrition on the table.

When feed is available, in both quantity and quality, households thrive: children drink milk, families eat better, and farmers sell surpluses. But behind this reality lies a persistent challenge: how to feed animals adequately throughout the year.

Climate change, shrinking grazing land, and rising feed costs push farmers into seasonal shortages that undercut productivity. When pastures dry up or crop residues become scarce and less nutritious, animals lose weight, reproduction declines, and food security is threatened.

Moving beyond blanket recommendations

Traditional feed interventions often prescribe “one-size-fits-all” solutions, e.g. planting a specific forage or feeding commercial supplements. But these approaches often fail to ask the right questions: Do farmers have access to markets, seeds, land, or cash to buy concentrates? Who actually feeds the animals (men, women, or children)? How do seasonal workloads shape their ability to gather fodder? By ignoring these realities, many interventions miss the mark.

Our team in Madagascar wanted to flip the script: what if communities, with their own knowledge and priorities, were at the center of diagnosing problems and designing solutions? That’s where G-FEAST comes in.

Building local ownership and partnerships

G-FEAST is more than a diagnostic tool; it is a participatory journey. It combines focus group discussions, household surveys, and gender analysis to uncover what feeds are available for livestock throughout the year, who controls their use, who makes feeding decisions, and where the seasonal or structural feed gaps occur.

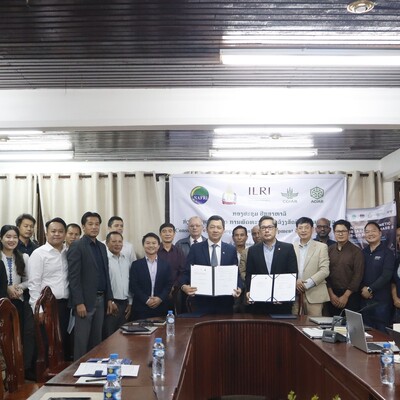

When the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) introduced G-FEAST in Madagascar in early 2025, the emphasis was clear: do not just assess, build local ownership. Rather than relying on external experts, we trained a national team drawn from the Centre National de Recherche Appliquée au Développement Rural – Madagascar (FOFIFA), Ministère de l’Agriculture et de l’Élevage (MINAE), and Fiompiana Fambolena Malagasy Norveziana: Centre de Développement Rural et de Recherche Appliquée (FIFAMANOR).

Over several days in Antsirabe, 23 researchers and practitioners learned not only how to apply the tool, but also how to engage with communities, respect gender roles, and generate actionable insights. They also reflected on gender roles in livestock feeding and discussed how to ensure women’s and youth’s voices were heard.

The outcome was more than a training. It was the creation of the G-FEAST Madagascar team; a diverse group committed to putting farmers and their communities at the center of feed interventions. What began as capacity building quickly became a catalyst for lasting partnerships as colleagues discovered complementary strengths, exchanged field stories, and built bonds that would carry the work forward. The training was not the end. It was the beginning.

Taking G-FEAST to the field

The first field exercise in Antsirabe II District marked a turning point. The trained team sat with men and women farmers separately. Farmers mapped seasonal feed calendars, debated why some households’ livestock thrived while others struggled, and revealed the hidden labor women contribute daily to feeding animals.

One G-FEAST training participant reflected: “We listened to farmers describe how they feed their animals across seasons, what forage species they prefer and why, and which family members are responsible for collecting fodder. We asked what changes they have noticed in feed availability over the past decade and how climate variability affects their herds. This participatory diagnosis allowed us to map the feed system from the perspective of those who live it every day and those exchanges were eye-opening.”

For many, this was not just data; it was a mirror. Seeing the system mapped in such detail sparked conversations on what could be done differently, and by whom.

Scaling collaboration across Madagascar

Encouraged by the Antsirabe experience, ILRI and partners expanded G-FEAST to five diverse regions: Vakinankaratra, Boeny, Vatovavy Fitovinany, Sava, and Atsimo Andrefana. Each region brought its own realities: coastal feed systems in the northwest, cassava-dominated diets in the south, and dairy-focused systems in the central highlands. Yet the method remained the same: listen, analyze, co-design.

The result was a remarkable collaboration where national researchers, extension agents, and communities worked hand in hand. Local teams not only mastered the tool, but also learned to ask the right questions, interpret results, and propose solutions that resonated with farmers.

Empowering local actors and shaping future interventions

By leading the diagnosis themselves, the Malagasy team gained confidence in analysing feed systems and recommending context-specific interventions. They started to understand that:

- Better feeds mean not just more biomass but better nutrition, leading to healthier animals and improved family diets.

- Climate resilience is linked to feed, through drought-tolerant forages, diversified resources, and reduced emissions.

- Feed interventions can empower youth and women by creating enterprises in feed production and fodder markets, while recognizing women’s vital labor.

- Better feeds ultimately mean better incomes: faster animal growth, more milk, and higher prices at market.

Perhaps the most important outcome has been a shift in mindset. Feed challenges are no longer seen only as technical problems for agronomists or livestock experts. They are now understood as deeply social, shaped by who feeds the animals, whose knowledge counts, and who benefits from change.

Looking ahead: from diagnosis to action

G-FEAST is not an end but a starting point. In Madagascar, the assessments generated a wealth of data and stories that are guiding the following next steps:

- testing forage species that align with farmers’ preferences,

- training farmers on good feeding practices, feed processing and conservation innovations,

- developing community-based feed enterprises, led by women and youth; and

- advocating for policies that recognize livestock as key to improving food security and nutrition.

Our partnership with FOFIFA, MINAE, and FIFAMANOR has grown beyond a single project into a shared commitment to building resilient feed systems. Better feed is more than fodder. It is nutrition for families, resilience against climate shocks, empowerment for youth and women, and prosperity for communities.

The journey with G-FEAST in Madagascar is still unfolding. But one lesson is already clear: when we invest in local teams and trust communities to co-lead the process, we do not just diagnose feed problems, we build pathways to lasting change.

And perhaps that is the real story: not the tool itself, but the people who now carry it forward, confident, connected, and committed to transforming livestock systems in their own regions.

Better and climate-smart feeds mean better futures for communities.

You may also like

Challenging gender norms: Bringing gender-transformative approaches (GTAs) to livestock communities to the Northwest Highlands of Vietnam

ILRI News

“Maisha Makutano”, Kenya’s new edutainment series, features ILRI’s gender and livestock research

Related Publications

Harnessing community conversations for gender-responsive engagement in livestock management in Ethiopia: a methodological reflection

- Lemma, Mamusha

- Alemu, Biruk

- Knight-Jones, Theodore J.D.

CGIAR Science Program on Sustainable Animal and Aquatic Foods : Gender, youth and social inclusion area of work

- Achandi, Esther L.

Effects of livestock related gender roles on pastoral children and their implication to RVF risk exposure

- Mutambo, Irene N.

- Bett, Bernard

- Bukachi, S.A.